QUESTIONS: Can you think of license options that CC is currently missing that would benefit the open education movement? As the CC and GFDL licenses are incompatible, how can OCW content be legally remixed with Wikipedia content? Some people claim that the Creative Commons ShareAlike clause provides most of the protections people want to secure from the Creative Commons NonCommercial clause. What do you think these people mean, are they right, and why? Is copyleft good for the open education movement? Why or why not?

One license option that my partner and I have thought would be useful for certain of our own purposes is one that allows derivative use (commercially or NC) as long as the piece that is used is not the entire new work. This is similar to the Sampling license that allows a piece of the original to be used, but not the whole thing; however, in this case, we don’t mind if they use the whole thing; we just want the resulting piece to be something new. Essentially, we are happy for people to remix some of our works, but we don’t want them just reposting our works with no changes. (This is kind of the opposite of no derivs; we want only derivs for a certain category of works.)

I don’t know that this has particular relevance to educational works, but it may. For example, I think a license like this may assuage the concerns of some regarding commercial use. I think that many would be ok with commercial use providing that whatever reusers are selling is not just their work. If for example, I write an article, I might be fine with someone incorporating it into a much larger work and selling that. I would not, however, want to permit them to sell just my work alone.

Also, we need to think harder about what “commercial use” is in an educational context. Universities charge fees. Is using something licensed as NC in a university commercial? I would argue that it is. How about charging just enough to cover printing costs? There are a million examples of uses that are technically commercial but that wouldn’t be objectionable to most who specify NC. I am not suggesting that we cover all of those instances in NC licenses; I am suggesting that NC licenses be used more sparingly in educational contexts.

Regarding the question of the incompatibility of CC and GPDL, I don’t have an answer, but I hope someone will provide insight into this. I am currently starting a large new open project and want to put it on Wikibooks and am thinking through the licensing implications related to this.

One possible solution that Wikimedia Commons is offering is dual licensing, so, for example, you can license under GFDL and CC. I have been licensing my own photos on Wikimedia Commons this way, but at this point, this does not apply broadly to text articles in Wikipedia or Wikibooks.

The GFDL says ” A compilation of the Document or its derivatives with other separate and independent documents or works, in or on a volume of a storage or distribution medium, is called an “aggregate” if the copyright resulting from the compilation is not used to limit the legal rights of the compilation’s users beyond what the individual works permit. When the Document is included in an aggregate, this License does not apply to the other works in the aggregate which are not themselves derivative works of the Document.”

I have reread this several times now and am not sure exactly what this means, but it seems to me to allow for the aggregation of GFDL and CC work. I believe that GFDL is compatible with some CC licenses, most especially a CC-By-ShareAlike license. Dr. Wiley, can you clarify why these licenses would not be compatible? [I think I’ve answered my own question….the problem is with the license OCW has chosen, not all CC licenses.] Presumably, an aggregated work could be licensed under the license that has the most conditions (in this case GFDL, which in being more open requires more) as long as none of the conditions contradict licenses of other pieces in the aggregation.

In regards to the claim that the Creative Commons ShareAlike clause provides most of the protections people want to secure from the Creative Commons NonCommercial clause, I think they are two different things. I can produce Work A with a NC clause and Work B with a ShareAlike clause (but no NC clause). Work B could be incorporated into a commercial work that then must by virtue of my license be licensed as ShareAlike. The same is not true for Work A, which could never be used commercially.

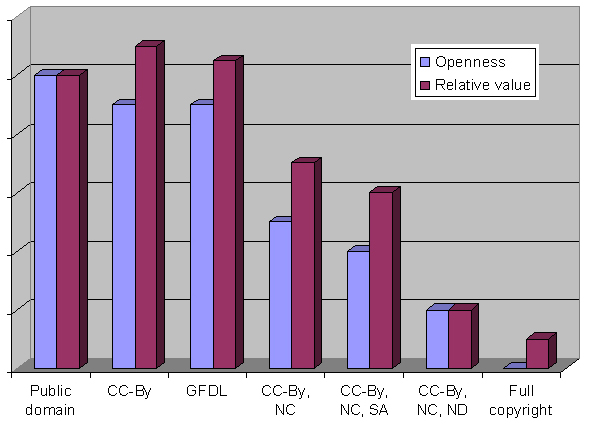

I think Share Alike is good for the educational community. I also think that allowing commercial use is beneficial for the community. However, I also think that each artist/author should be able to choose the license they wish, including NC, and for that to still be considered “open.” As there is more and more content available, market forces will give a heavier value weight to more truly open content.

These are complicated issues. I’m going to reread a few of these pieces and may add some resulting thoughts over the next few days.