One of my frustrations with mass collaboration in general and some wikis in specific is the lack of editorial direction. As a former book editor and software executive producer, I appreciate the role of a guiding vision and someone to make sure the work stays true to that vision. In many Web 2.0 works that involve many parties, I find that the vision is vague, if present at all, and the work of the many meanders as a result. In some works, this is less problematic, but in many, especially those in education, it leads to an end product that is not very valuable.

This point was brought to the forefront for me again by the recent post by Jeff Jarvis, which asks “Are editors a luxury that we can do without?” In the world in which everyone can publish, and many rely on news coverage that is more amateurish (though also more democratized), it strikes me that editors are more important than ever. I like Jarvis’ suggestion that one of the roles of the “new” editors is as curators.

There are many objections to the use of Web 2.0 applications and mass collaboration in schools. Many strike me as ridiculous, but one that merits serious consideration is the call for high quality content. In a mass collaboration environment in which everything can be edited by everyone, all types of content inaccuracies, as well as bogus or profane content, can and does appear. (I’ll leave aside, for the moment, my own feelings that kids need to be taught to how to discern this, screen content, and find alternative sources. This is a real 21st century skill.) At the most basic level, one role of an editor is to screen content for accuracy.

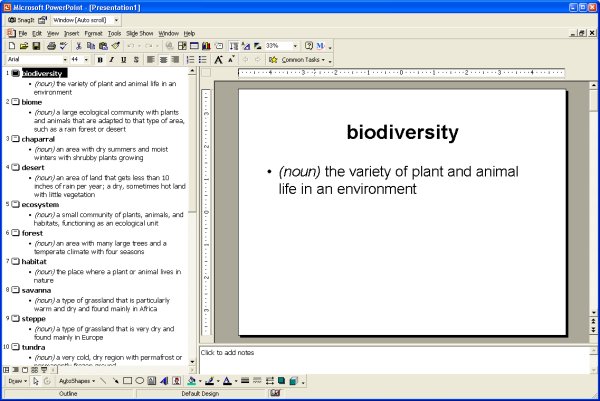

When we started on the kids open dictionary, one of our most important objectives was to produce something that is high quality and kid-appropriate. While we wanted to tap into the wisdom of a mass of people to create content, we also wanted to be able to exert some level of editorial control. Ultimately, a group of trusted experts will be evaluating each word, seeking changes, and deciding when it is time to “freeze” words. By producing products (ebooks, database dumps, etc.) that have gone through this process, we will be able to ensure a level of quality.

More importantly, we’re evolving a working editorial process at the dictionary that is somewhat subtle. Initially, we had an idea of what a dictionary for kids should be — simple, comprehensible, not comprehensive or exhaustive. We wrote some style guidelines, but didn’t expect them to be read by many (and I don’t think they have been). As people came and began writing definitions, it was clear that everyone came with a different idea of what a dictionary for kids should be. Some were very simple. Others resembled encyclopedic entries.

The beauty of a wiki is that you can edit. And believe me, it is easier to edit almost anything than to create it from scratch. We are hoping that through careful editorial attention, editing, and gentle guidance, this will evolve to a work that has consistently high quality content that is true to our vision.

So far, most of the editing has been done by our staff here. (It’s interesting that many others have added definitions, but few have edited existing ones. It may be because we are in an early phase of development.) I am hoping that over time, we get a cadre of core users who will embrace the vision and edit copiously to reach it. (I really like the style taken by this project which challenges users to improve upon content. I am wondering if something similar can be done with the dictionary.)